Greenock’s first Glebe Sugarhouse (and the fifth sugarhouse to be constructed in the town) was built sometime in 1811 or 1812. It was situated around Ardgowan Street, Clarence Street, Nelson Street and Crawford Street as this advertisement for its sale in 1814 shows.

The advertisement reads: -

“The Glebe Sugarhouse in Greenock

To be sold by public roup, within the Tontine Tavern,

Glasgow, on Wednesday the 28th day of September current, at 12 o’clock noon.

All and whole the GLEBE SUGARHOUSE, in GREENOCK, belonging

to the sequestrated estate of ROBERT TAYLOR and Co, Commission Agents in

Edinburgh, with the whole Utensils therein.

These premises extend to 230 feet in length, in front of Ardgowan

Street, 136 feet in front of Clarence Street, 19½ in front of Nelson Street,

and 140½ feet in front of Crawford Street; and, as the buildings were

originally erected for a Sugarhouse, they are particularly well adapted for

carrying on the trade of sugar refining.

For further particulars application may be made to William

Mylne, merchant in Leith, the trustee; John Muir, writer in Greenock; or Thomas

Johnston, 37 Albany Row, Edinburgh, in whose hands are the title-deeds and

articles of roup.”

That may be a bit confusing at first, because today Nelson Street and Ardgowan Street are in the west end of the town, Crawfurd Street no longer exists, and Clarence Street is generally now known as Container Way. So where was this Glebe sugarhouse? It is all in the name – Glebe. In past times, a glebe was “a portion of land assigned to a parish minister in addition to his stipend”. So, from that we would assume that this Glebe had to be near Greenock’s main church. That’s exactly where it is. Check out the map below. There you will see the Old West Kirk at the eastern section of the clip and the other streets mentioned in the advertisement.

The sugarhouse was started by William Leitch & Company. In August 1828 many of the works in the town were “inspected” by Earl and Lady Cathcart accompanied by Sir Michael and Lady Shaw Stewart. A newspaper report describes the reason for the visit was “to examine the progress of improvements in the town during the long period which he had been absent from it – no less than fifty years”!

In July 1834 the workers at the sugarhouse went on strike demanding higher wages. They marched through Greenock stopping at all the other sugarhouses in the town conferring with the workers in these in the hope that they would join them. Their employer, William Leitch demanded that they go back to work, threatening to bring in workers from Liverpool to take their places. They eventually returned to work. (The company also had a refinery in Liverpool.)

By 1843 the Glebe sugarhouse was owned by Connal and Parker. When Matthew Parker retired it became known as E Connal & Co. Ebenezer Connal had previously been involved with the Finnieston brewery and distillery along with other members of his family.

In 1849 disaster struck. At four o’clock in the morning of Sunday 22 April, the alarm was raised that a fire had broken out at the sugarhouse in the Glebe belonging to Ebenezer Connal & Co. Fire engines were quickly on the scene and quickly got to work hosing down the western end of the building where the fire had originated. The building was a mass of flames the scene described as “one of terrific grandeur”.

After two hours ablaze, the roof collapsed on the three-storey building, taking all the sugar making equipment in its path down with it. The firemen worked hard to contain the fire and successfully stopped it from spreading to nearby buildings. 150 puncheons of molasses were rolled out and stored safely away from the burning building. Clarence Street, opposite the sugarhouse was covered with several inches of boiling molasses which had escaped from the building. Barricades were erected in the event of the rest of the building collapsing and to prevent pilfering. The total loss incurred was believed to be about £20,000 which included building, machinery, and stock. Fortunately, everything was insured, no lives were lost and no injuries were incurred. Unfortunately, the damage meant that many of the sugarhouse workers no longer had jobs to go to.

The refinery was not rebuilt for some time. In 1850 what remained was sold including: -

“Animal Charcoal, Charcoal Cisterns, Steam Boilers, Melting Pan, Heaters, Steam

and other Pipes, Brass Valves, a quantity of Copper, and a great variety of

other articles used in the process of Sugar Refining …”.

In 1853 the ruins had been replaced by a large warehouse used by Thorne & Sons as a bonded store holding 3000 puncheons (a puncheon was a barrel holding 70 gallons). The premises had obviously been enlarged as the dimensions are now quoted as:-“ It forms a square fronting the entire length of Ardgowan-street by about 235 feet, and of Nelson-street by about 195 feet, with a front to Clarence and Crawford-streets of about 140 feet”. The building remained as warehouse accommodation.

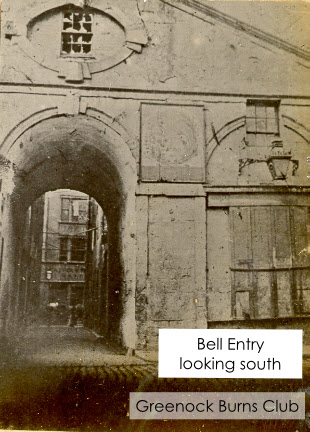

Old West Kirk Glebe

|

| Source - Greenock Burns Club |

The Glebe took up quite a considerable space when it was laid out. It is described as "commencing

at the old manse, passing outside the burying-ground wall, crossing what is now

Crawfurd Street, comprehending a portion of the area lying between Crawfurd

Street on the north and West Blackhall Street on the south, then turning

north-westward it meets what is now Boyd Street, down Boyd Street to Clarence

Street, and thence turning east ward along the south side of Messrs. Laird

& Co.'s ropework to the point first mentioned". The original manse was much nearer the church at the east end of Clarence Street.

At that time there were eight streets in the Glebe. Their names reflect both local and national interests. As for the two main streets, Clarence Street was named after HRH the Duke of Clarence and Crawfurd Street named after Baillie Hugh Crawfurd. Nelson Street so named after the famous Admiral Lord Nelson. Ardgowan Street named as a compliment to Sir John Shaw Stewart.

To save confusion when the two Ardgowan and Nelson streets existed at the same time, they were identified as Ardgowan Street (glebe) or Ardgowan Street (west).

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)